In his new book, Overdiagnosed: Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health

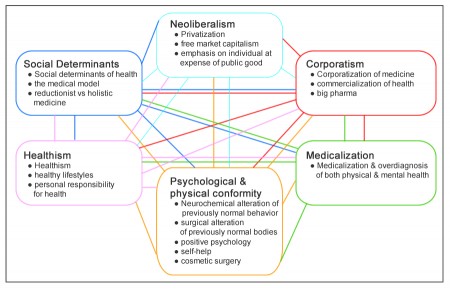

In his new book, Overdiagnosed: Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health , Dr. H. Gilbert Welch enumerates how the cutoff points that determine whether a patient should be treated for a disease – diseases such as high blood pressure, diabetes, osteoporosis — have been creeping inexorably lower over the years.

, Dr. H. Gilbert Welch enumerates how the cutoff points that determine whether a patient should be treated for a disease – diseases such as high blood pressure, diabetes, osteoporosis — have been creeping inexorably lower over the years.

Take diabetes. The cutoff point used to be a fasting blood sugar level of greater than 140. In 1997, the number was lowered to 126. This immediately created 1.7 million new diabetes patients.

In a highly publicized study that began in 2003, one group of patients with type 2 diabetes received “intensive therapy” to make their blood sugar “normal.” The control group – the other half of over 10,000 patients – received treatment to lower their blood sugar, but not to the new normal level. The trial was stopped in 2008 when it became clear that there was about a 25% increased risk of dying for the intensive therapy group.

Dr. Welch’s comment on this: “If it’s not good to make diabetics have near normal blood sugars, then it’s not good to label those with near normal blood sugar diabetics. Why? Because doctors will treat them. People with mild blood sugar elevations are the least likely to gain from treatment – and arguably the most likely to be harmed.”

High blood pressure (hypertension) was also redefined in 1997. Instead of the cutoff points being 160 systolic over 100 diastolic, the numbers dropped to 140 over 90. This created 13.5 million new patients.

The definition of high cholesterol (hyperlipidemia) changed following a 1998 clinical trial. The definition of “abnormal” total cholesterol fell from 240 to 200. This created 42.6 million new patients, an increase of 86% over the previous number of patients.

It’s the same with the definition of osteoporosis. A bone mineral density X-ray produces a T score. It’s a way to compare an individual’s bone density to what’s considered “normal.” For women, normal is defined as the bone density of an average white woman aged 20 to 29 (a T score of zero.) If your T score is less than zero, it’s assumed you have an increased risk of fracture.

In 2003 the definition of osteoporosis changed from having a T score less than -2.5 to less than -2.0 (i.e., closer to normal). This created 6.8 million new patients, an 85% increase in those now eligible for treatment with drugs that turned out to have significant side effects – as virtually all drugs do. Read more