Implementing the discoveries of modern brain science raises ethical issues. For example: (emphasis added)

Implementing the discoveries of modern brain science raises ethical issues. For example: (emphasis added)

Issues of personhood and authenticity, for example, have become hotly debated among neuroethicists as pharmaceuticals developed for improving mental health disorders, sleeping disorders, or attention disorders in children are now being consumed at high rates as off-label “cognitive enhancers” to boost mood, memory, and alertness. If these drugs, or substances like oxytocin, become the Viagra of daily functioning and create new benchmarks for productivity, wakefulness, and emotional love, what will happen to the fabric of society and the character of our interactions with one another? Are these altered states a genuine reflection of a new and improved “me” or “we”, or some transient drug-induced condition that thoroughly confounds what we inherently value? Will we be coerced into conforming to a wave of drug intervention in the ever expanding, do-it-yourself, self-help world? The race for cognitive enhancers poses questions of social justice as well. Will the opportunity gaps between those who can afford them and those who cannot be widened or narrowed? …

[H]ow shall scientists, physicians, legal scholars, policy makers, and society at large manage new tests that may soon be able to forecast with acceptable reliability unacceptable levels of risk for aggression, sociopathy, psychopathy, and suicide?…

With advanced capabilities, will an integrated understanding of the genetics and brain biology of these conditions [Alzheimer’s, schizophrenia, addiction, anxiety, stress] … plunge those affected into fatalistic states of hopelessness out of which they feel they cannot ever emerge?…

Entrepreneurs will surely lose no time in selling the technology directly to consumers who may be curious for what they interpret to be a neurogenetic signature or fearful about their neurogenetic status. What, and how much, would you want to know? At what personal and financial cost?

The quotations are from an article in The Lancet entitled “Empowering brain science with neuroethics.”

We neglect the real moral implications at our peril

A response to the article by Peter Whitehouse, entitled “Empowering whom? Neuroethics at its limits,” points out that neuroethics appears to be “narrowly focused on currently scientific perspectives, and morally unimaginative about the huge challenges of brain and health facing the planet.”

Like its parent field, bioethics, neuroethics is not attending to the issues of environmental brain health and of social injustice. Instead, it is empowering science (and scientism) by focusing on the ethical implications of mind-reading machines and mind-enhancing drugs and assuming that they are just around the corner and hence deserving of our attention.

Permit me just an ounce of neuroscepticism about this agenda, and a pound of concern about being distracted from the more important health issues at work in the world that make us an endangered species, such as global climate change. Maybe the field of neuroethics needs a deeper form of cognitive enhancement itself, and with that more attention to its own moral scope.

The same criticism could be leveled against medicine in general. In confining its focus to the latest theoretical discoveries and technological advances, medicine neglects the environmental causes of disease and the socially unjust distribution of disease. It’s rare to see this issue raised in professional discussions of the state of medical science.

I’m reminded of a statement by Kwame Anthony Appiah in Experiments in Ethics, where he talks about how we allow a description of a problem to determine our options. (emphasis in original)

We can call this the package problem. In the real world, situations are not bundled together with options. In the real world, the act of framing – the act of describing a situation, and thus of determining that there’s a decision to be made – is itself a moral task. It’s often the moral task. Learning how to recognize what is and isn’t an option is part of our ethical development. … To understand what’s wrong with murder is, in part, to be disinclined to take killing people as an option. … In life, the challenge is not so much to figure out how best to play the game; the challenge is to figure out what game you’re playing.

All too often in the health care industry, the best way to play the game is to maximize the profits of the major players. That perspective loses sight of the real game we’re playing, which is to keep people alive and healthy.

Related posts:

Healthy lifestyles serve political interests

The death of Wang Bei: Cosmetic surgery as a moral choice

A raffle for free (human) eggs

Resources:

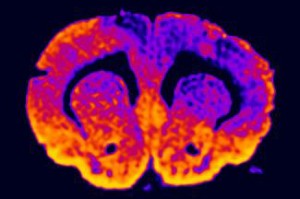

Image: George Mason University

July Illes, Empowering brain science with neuroethics, The Lancet, October 16, 2010

Peter Whitehouse, Empowering whom? Neuroethics at its limits, The Lancet, February 5, 2011

Kwame Anthony Appiah, Experiments in Ethics

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Neuro Now, healthculture. healthculture said: The ethics of a neuroenhanced future http://j.mp/hYrGNH Does a narrow focus on the science distract us from more important health issues? […]