When I want to know more about a medical condition, my first Internet destination is the Mayo Clinic’s website. It seems both reputable and decidedly non-alarmist.

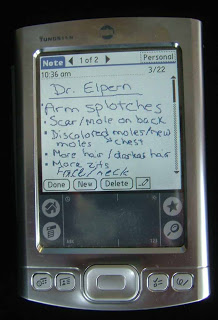

Each condition is organized into a series of information packets: definitions, symptoms, causes, risks. There’s invariably a section called “Preparing for your appointment.” Without fail, it recommends that you make a list of your symptoms. Here’s an example:

Before your appointment, make a list that includes:

- Detailed descriptions of your symptoms

- Information about medical problems you’ve had in the past

- Information about the medical problems of your parents or siblings

- All the medications and dietary supplements you take

- Questions you want to ask the doctor

Once you’ve begun interacting with your doctor, it can be easy to forget something you’d intended to ask.

I was somewhat surprised, then, to learn that some doctors are decidedly irritated when a patient brings a list to an appointment. Dr. Suzanne Koven discusses this in a Perspective piece in NEJM: The Disease of the Little Paper.

Her father was a doctor

This is a very personal essay. For example, Dr. Koven relates that her father was also a doctor, and, in his later years, he enjoyed telling her self-flattering anecdotes.

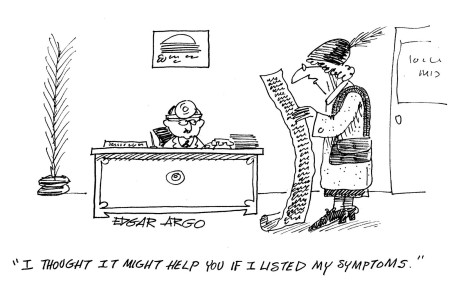

The reminiscence I bristled at most, though, was about ladies — always they were “ladies” — with something he called la maladie du petit papier: the disease of the little paper. They would come to his office and withdraw from their purses tiny pieces of paper that unfolded into large sheets on which they’d written long lists of medical complaints.

“You know what I did then?” Dad asked. I did, but I let him tell me again anyway. “I’d listen to each symptom carefully, and say `yes’ or `I see’ — that’s all. And when a lady finally reached the end of her list, she would say, `Oh doctor, I feel so much better!’ The point is, all those ladies needed was someone to listen.”

Perhaps there’s something about Dr. Koven’s father that contributed to her attitude towards lists, as I’m tempted to speculate below.

Those irksome, irritating lists

Dr. Koven goes on to relate that she is familiar with these lists from her own experience and that they sometimes irritate her, “as they do many doctors.” Really? Actually, yes. Here’s a study (from 1994) of doctors’ attitudes: Written lists in the consultation: attitudes of general practitioners to lists and the patients who bring them. The attitude towards ladies persists: 75% of GPs thought patients who brought lists were middle-aged and female.

Dr. Koven goes on to relate that she is familiar with these lists from her own experience and that they sometimes irritate her, “as they do many doctors.” Really? Actually, yes. Here’s a study (from 1994) of doctors’ attitudes: Written lists in the consultation: attitudes of general practitioners to lists and the patients who bring them. The attitude towards ladies persists: 75% of GPs thought patients who brought lists were middle-aged and female.

Dr. Koven finds it “irksome” to see her name at the top of a list, “evidence that to my patient I am often merely another stop in a series of tedious errands.”

Why should these lists bother her, she asks? She knows it’s only sensible to bring lists to appointments, considering how little time is now allocated to each visit. She knows patients are encouraged to do this. She cites a 1985 study (by John F. Burnum) that concluded it is not a sign of an emotional disorder to make a list of symptoms. She writes:

I wonder if I resent these lists because they threaten me. The “control” that Burnum thought patients reasonably sought is wrested, in part, from the doctor. When a patient pulls out that little piece of paper, I feel a shift in the exam room: the patient taking charge of the agenda, my schedule running late, the reins of the visit loosening in my hands.

The narcissistic parent

I was struck by a detail Dr. Koven chose to relate about her father.

“Seen any great cases?” he’d ask. …

I’d explain — again — that I was a general internist, not a specialist as he had been, and derived my professional satisfaction from long and close relationships with patients and not from making obscure diagnoses.

He would give me a pitying look and shrug. Then he’d tell me some anecdote in which I heard him imply that he was more resourceful, wiser, and more devoted to and beloved by his patients than I could ever hope to be.

I must admit, I can only sympathize with a daughter who’s subjected to what appears to be a narcissistic parent.

My own example: One of my priorities in choosing a college was to get far away from home (3,000 miles). And I was not inclined to introduce boyfriends to my mother. But one college summer, when I’d returned home and was looking for a job, a boyfriend from the other coast unexpectedly showed up at my door. My mother proceeded to tell him: “I was so much better looking than Janice when I was her age.” What?

The message a child gets from a narcissistic parent is that you can never be good enough. It’s not a childhood likely to instill confidence (I’m just a stop on a series of “tedious errands”) or a sense of control (the list threatens to “wrest control” from the doctor). But it would be unwise, and inappropriate, for me to speculate on Dr. Koven.

Patients worry about wasting a doctor’s time

I’m unlikely to know personal details about my own doctor that would provide clues to her attitude towards a list of questions. Should I consult my list surreptitiously? Should I inquire about her attitude — that would be of interest to me, but not a good use of her time. Patients have become conscious of not wasting their doctor’s time, especially when they read of doctors who admit: “[I am] exasperated by parents who bring in a child with a cold.” Or this, from a wonderful post by Jonathon Tomlinson on a proposed NHS campaign intended to dissuade patients from “unnecessary” visits: “Parents of young children … feel ashamed and stigmatised if they are made to feel they are wasting professionals’ time.”

Given the constraints on doctors’ time these days, I can understand that they are wary of the doorknob question: when the patient says “oh, just one more thing” as the doctor is walking out the door. A question on my list would undoubtedly get a better answer than a question asked when the doctor’s hand is on the doorknob. Doctors, I’m sure, would prefer this too.

So I say, if you need a list, don’t hesitate to use it. La maladie du petit papier be damned.

Related posts:

The emotional burdens of patient care

Candid comments from the medical profession

Are doctors tired of practicing medicine?

The doctor/patient relationship: What have we lost?

Contempt and compassion: The noncompliant patient

Get thee glass eyes

Image source:

Cartoon: The Celiac Shack

List on phone: vgrd-Bleacher-Report

References:

Suzanne Koven, The Disease of the Little Paper, NEJM, December 11, 2014, Vol 371, No 24, pp 2251-2253 (OA)

J Middleton, Written lists in the consultation: attitudes of general practitioners to lists and the patients who bring them, The British Journal of General Practice, July 1994, Vol 44, No 384, pp 309–310 ($)

John F. Burnum, La Maladie Du Petit Papier — Is Writing a List of Symptoms a Sign of an Emotional Disorder?, NEJM, September 12, 1985, Vol 313, pp 690-691 ($)

Anonymous, What I’m really thinking: the GP, The Guardian, January 17, 2015 (OA)

Jonathon Tomlinson, How much do you cost the NHS?, A Better NHS, October 29.2014 (OA)

Karyl McBride (2008), Will I Ever Be Good Enough?: Healing the Daughters of Narcissistic Mothers

M. Spencer Green, Doctors discuss ways of avoiding ‘doorknob’ situations, USA Today, March 27, 2005 ($)

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.