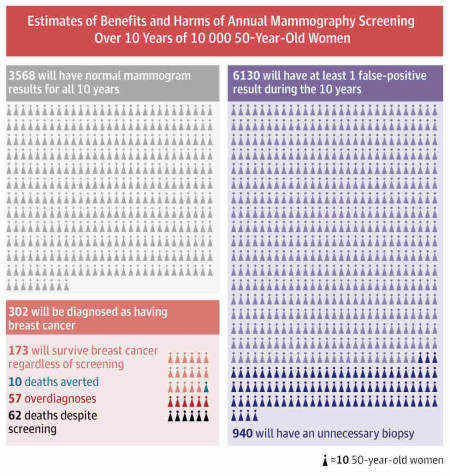

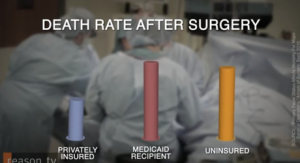

Back in June of 2009, when Congress was just beginning to formulate and debate the Affordable Care Act, Atul Gawande wrote an article on the rising (and exorbitant) cost of US health care. He focused on how waste contributes to cost — not just the usual fraud, high prices, and administrative fees, but unnecessary care: Drugs that are not helpful, operations that do not make patients any better, scans and tests that not only have no benefit, but often lead to harm. Waste accounts for a third of health-care spending. More disturbingly, it can cost people their lives.

Gawande used the town of McAllen, Texas to illustrate his case. McAllen had one of the highest costs in the nation for Medicare — twice as high as El Paso, another Texas border town with similar demographics. And it’s not as if patients in McAllen were receiving better care. Compared to El Paso, patient care was similar or worse.

It turned out that many specialists in McAllen had financial stakes in home-health-care agencies, surgery and imaging centers, and the local for-profit hospital. One local doctor told Gawande: “Medicine has become a pig trough here. … We took a wrong turn when doctors stopped being doctors and became businessmen.” Read more