It’s always hard to be sure about these things, but I think the reason I decided to take a ‘sabbatical’ from blogging last July was that I was interested in too many seemingly unrelated topics. Writing about all of them left me feeling like I never got to the ‘meat’ of any one of them. And I couldn’t convince myself to focus on just one or two things, since that would mean abandoning the others, which I was unwilling to do.

Now that I’ve taken the past year to read and reflect, I find – duh! – that my interests are not as unrelated as I’d assumed. In hindsight, I should have realized this long ago, but, alas, I did not. I’m writing this post to clarify to myself what I now see as the common threads that connect my interests.

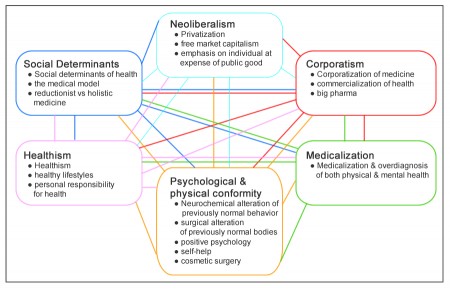

Here is a diagram that groups my interests into six categories. (Click on the graphic to see a larger image.)

Four of the six categories relate to all five of the others. The two outliers (neoliberalism and medicalization) are not as directly related as I feel the others are.

This post ended up being so long that I’ve divided it into four parts. The first two contain definitions, part three spells out the connections, and part four explains why these topics are especially meaningful to me.

Healthism

Healthism (excessive, usually anxious preoccupation with health) frequently motivates healthy lifestyles (diet, exercise, not smoking, etc.). Failure to observe healthy lifestyles has been used (medically and politically) to blame individuals who are ‘insufficiently’ responsible for their health (personal responsibility for health).

Medicalization

When a normal bodily process/characteristic (menopause, height) or a previously normal behavior (sadness, shyness) is no longer considered normal but something worthy of medical diagnosis and treatment, that’s medicalization.

Disease mongering often coincides with medicalization. When a pharmaceutical company generates anxiety about a benign condition (for which it just happens to sell a product), that’s disease mongering. Listerine was a relatively unsuccessful product for dandruff until Warner-Lambert increased awareness of something that sounds like a serious medical condition: halitosis. The process of turning heartburn into gastroesophageal reflux disease (better known as GERD) illustrates both medicalization and disease mongering.

Another variation on disease mongering is to suggest to the well that they may unknowingly suffer from an existing disease. “Do you know your number?” (for cholesterol) campaigns are an example. Another one: Direct-to-consumer cardiac screening and whole body scans.

Overdiagnosis is a less disparaging, more medically acceptable term for how seemingly healthy people can acquire a disease label overnight. When the cut-off point for diagnosis of a disease (high blood pressure, diabetes) is lowered, millions of people transition from healthy to sick. This often happens when a new drug becomes available.

Of course the authors of an updated clinical guideline that accomplishes such a transition would not call this overdiagnosis. They would say that people who believed they were healthy were — with the wisdom of hindsight — actually sick. The assessment of disease by the use of surrogate markers (cholesterol level, blood sugar level) rather than endpoints (morbidity, mortality) leaves a large gray area into which overdiagnosis creeps.

Overdiagnosis also happens, innocently enough, as a side-effect of modern imaging technology. A diagnostic screening that seeks to explain symptoms in the lungs may reveal incidentalomas (tiny, asymptomatic tumors that would never amount to anything) in near-by parts of the body. This can lead to unnecessary and even harmful treatment.

Overdiagnosis of mental health conditions has produced epidemics of depression, social anxiety, and childhood disorders. This phenomenon has been especially pronounced since the 1980 revision of the American Psychiatric Association’s reference work, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III).

It’s easy and common to blame financial and professional interests for the prevalence of medicalization, disease mongering, and overdiagnosis, but surely this could not have happened without a susceptible and receptive public. Some aspects of healthism may explain our willingness to regard the risk of disease as sufficient reason to medicate our surrogate markers. As for the enormous increase in psychiatric disorders, significant social changes have undoubtedly altered the individual’s self-perception (see Is the prevalence of depression related to the modern empowerment of the individual?).

Psychological & physical conformity

This category may seem a bit of a grab bag at first. What unites its contents is the use of medicine and psychiatry to ‘help’ individuals conform to social pressures.

‘Better than well’ psychopharmaceuticals (Prozac, Paxil, etc.) align an individual’s personality with prevailing cultural values. When a culture is competitive, aggressive, and garrulous, shyness and sadness are socially undesirable. There’s a pill for that.

In addition to culturally desirable personalities, there are culturally desirable bodies. Aesthetic cosmetic surgery aligns individuals with the physical appearance currently favored by their culture. This allows individuals to increase their cultural capital, as Bourdieu would say.

I include in this category the happiness/positive psychology movement and the self-help industry, since they also help individuals conform to prevailing social expectations. It’s no coincidence that positive psychology supports the current economic interests of society (see, e.g., this description of the medical profession’s responsibility to boost worker productivity by increasing the happiness of patients).

Continued in part two, where I describe the remaining three topics: corporatism, neoliberalism, and the social determinants of health.

Related posts:

On sabbatical

What is healthism? (part one)

What is healthism? (part two)

Healthy lifestyles serve political interests

The politics behind personal responsibility for health

Medicalization then and now

How the pharmas make us sick

From healthism to overdiagnosis

Guest post: Is the prevalence of depression related to the modern empowerment of the individual?

Overdiagnosed and overprotected children

Why are we so willing to undergo cosmetic surgery?

The duty to be happy

References:

Kimberly M. Lovett and Bryan A. Liang, Direct-to-Consumer Cardiac Screening and Suspect Risk Evaluation (PDF), JAMA, June 22/29, 2011, vol 305, no. 24, pp 2567-2568

Micki McGee, Self Help, Inc.: Makeover Culture in American Life (2007)

William Davies, The Political Economy Of Unhappiness, New Left Review, 71, September-October 2011

Very interesting post, and I’m looking forward to further installments. Earlier this year I started a blog which fizzled, partly due to my feeling overwhelmed about writing something “on-topic” every day or so … I think the problem was that “on-topic” is a much wider area than I initially thought! Thanks for the motivation.

Thanks for your comment, Theresa. I’m glad that particular issue resonated with you. Blogging easily triggers introspection if you’re the self-reflective type. This gives rise to a topic I think of as ‘The self-conscious blogger.’ There’s the whole question of where to draw the line between private and public, for example.

What does it mean to be ‘on-topic’? Something I find helpful is this quotation from Kenneth Atchity. (http://amzn.to/LWzhRd) He’s talking about why you shouldn’t worry about originality when writing, but the same logic applies to being ‘on-topic’ in a blog. Something is ‘on-topic’ because it speaks to you. I find blogging is an opportunity to clarify who I am.

“You needn’t worry about your originality, even if your work is hugely based on that of others. What’s original is your assembly, your discovery of the “natural shape” (which is the combination of your mind’s interests and the shape of the subject itself): your perspective, your vision of the matter.”

I loved your most recent post with the photo of the 86-year-old gymnast! (http://bit.ly/LwJthQ) Now that’s universally on-topic!