The quality of health care depends on many things, but certainly medical education is uniquely significant. Following four years of medical school, the additional years of internship, residency, and fellowship are not simply a time for acquiring the latest insights into the nature and treatment of disease. This is when fledgling doctors imbibe the values and priorities of the medical profession from the attending physicians who mentor them. If attendings have no time to mentor the doctors they are presumably training, the quality of doctors who emerge from such a system will suffer. And if the priority of an academic medical center is to increase profits rather than care for patients, patients will also suffer, first at the hospitals associated with these centers and later as patients of the doctors who trained there. The decline in the residency system for training doctors is the subject of Kenneth M. Ludmerer’s Let Me Heal: The Opportunity to Preserve Excellence in American Medicine.

From mentorship to profits

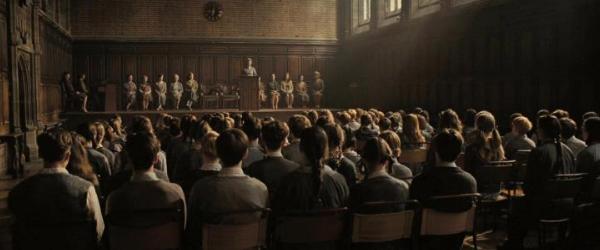

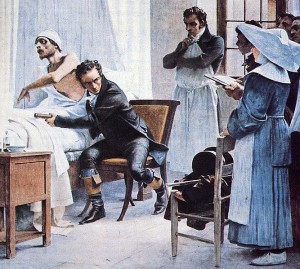

Sir William Osler established his ideal of medical training at Johns Hopkins Hospital in the 1890s. The guiding principle was that doctors should learn to care for patients under the close supervision of highly experienced attending physicians. Right up to WWII, the highest priority of teaching hospitals remained education. Faculty members formed intense mentorships with their students, often lasting a lifetime. Lara Goitein, in an essay/review of Let Me Heal, writes: Read more