The Affordable Care Act (ACA, aka Obamacare) will expand insurance coverage to millions of Americans (for example, to individuals with pre-existing conditions). Having insurance, however, does not mean a primary care physician will be willing to take you on as a new patient. There are multiple reasons for this, as discussed in a recent article in JAMA, Implications of new insurance coverage for access to care, cost-sharing, and reimbursement (paywall).

The Affordable Care Act (ACA, aka Obamacare) will expand insurance coverage to millions of Americans (for example, to individuals with pre-existing conditions). Having insurance, however, does not mean a primary care physician will be willing to take you on as a new patient. There are multiple reasons for this, as discussed in a recent article in JAMA, Implications of new insurance coverage for access to care, cost-sharing, and reimbursement (paywall).

We no longer live in the Marcus Welby days of a medical practice that has only one or two doctors. The “vast majority” of primary care practices, however, have only 11 or fewer physicians (according to JAMA). Many of these practices are already at or near capacity, which means that adding new patients may require additional expenses (staff, office space, equipment). For small practices, the decision to add new patients is first and foremost a business decision: Will the increased income cover my increased expense? Here are some of the things the “vast majority” of providers will be thinking about:

- The ACA lowers the cost of health insurance for many individuals, in particular, for people with relatively low incomes. These patients, however, will pay more for health care itself due to higher co-pays (that part of the cost not covered by insurance) and higher deductibles (the maximum annual out-of-pocket expense). In the past, the main burden of collecting fees was on insurance companies. Under the ACA, it may be health care providers who are faced with a “collection burden.”

- Related to this, should these new, low income patients be trusted to pay later? That is, can they be billed or should payment be required at the time of service? That could mean an uncomfortable situation if a patient shows up in obvious need of care, but doesn’t have enough cash or a valid credit card to pay for it on the spot.

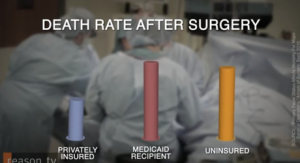

- The ACA expansion of Medicaid coverage is expected to add more than 12 million eligible patients. Medicaid does not reimburse physicians at the same rate as private insurance. Both Medicare and Medicaid reimburse doctors at lower rates than private insurance does, but Medicaid pays a whopping 41% less than Medicare (on average). And then there are the assumptions physicians may make about the financial and personal responsibility of Medicaid patients: “In addition to reimbursement, physicians have cited payment delays, administrative burden, and missed appointments as reasons for not accepting new Medicaid patients.”

- To overcome the reinbursement disincentive, the ACA increases Medicaid payments to the level of Medicare for two years (2013-2014). The primary care physician must ask: Will this be “worth the risk of adding staff and additional space to accommodate new Medicaid patients?”

- A complicating factor here is an ethical (and legal) one. Doctors cannot simply stop seeing Medicaid patients once the two years are up and reinbursement rates go down. There are “continuity of care” regulations. A patient can stop seeing a doctor, but doctors are not supposed to deny service to an existing patient.

- A somewhat more subtle issue involves measuring quality of care (qualities such as effectiveness of care, patient safety, timeliness of care, patient centeredness). Increasingly, both government and private insurers require that primary care practices submit reports on quality measures. Starting in 2015, the ACA makes quality measure reporting mandatory for Medicare. By 2017, physicians must report on 138 individual quality measures or they will be paid less. Reinbursement rates can be increased or reduced depending on the quality of a practice’s performance. This could have unintended consequences. “Clinicians may avoid seeing patients with complex health issues whom they fear might reduce their overall performance scores.”

- Whether or not a patient already has “complex health issues,” physicians may prefer not to see patients whose socioeconomic status is not conducive to good health:

Transportation problems and socioeconomic status are among the factors associated with missed appointments and link nonattendance to poorer outcomes. If physicians perceive, rightly or wrongly, new patients insured through Medicaid or exchange [i.e., ACA] products as less likely to adhere to treatment recommendations or to keep scheduled appointments, the number of practices not accepting these new patients could increase.

What this means is that universal health insurance in the U.S. (if we should ever be so fortunate as to attain that goal) will not mean equal access to health care. Even if reimbursement rates were equal for all patients, there would still be the question: Will this be a non-compliant patient who will reduce my income (and reputation) by lowering my quality of care score?

It seems to me what we have here is an example of how an acknowledgement of the social determininants of health actually increases inequality. As I’ve argued before, we cannot expect the social determinants of health to be addressed through the health care system. Instead,

We need to figure out a way to liberate health from the financial interests that drive health care. Until then we’re stuck with a system that cares more about profiting from the narrow agenda of scientific medicine than it cares about improving health.

Related posts:

Why medicine is not a science and health care is not health

The Dreams of the Founders of Family Medicine

The doctor/patient relationship: What have we lost?

Contempt and compassion: The noncompliant patient

What gets lost in the bureaucratization of medicine

From MD to MBA: The business of primary care

Physician as lone practitioner

Out of Practice: The demise of the primary care practitioner

Are doctors tired of practicing medicine?

Doctors in the trenches speak out – Part One

Déjà vu: Historical resistance to the inequities of health

Health inequities: An inhumane history

Health care inequality: The US vs. Europe

Image source: InterAlia

References:

A Everette James III, Walid F. Gellad, Brian A. Primack, Implications of new insurance coverage for access to care, cost-sharing, and reimbursement, The Journal of the American Medical Association, January 15, 2014, pp 241 – 242

Jan,

Thank you for this. You’ve raised so many key issues about the results of the curious amalgam known as the ACA: strapping government requirements on insurance, not care, within the framework of medicine (not even health) as a private commodity with massive public repercussions. In effect, what we’ve done is consign millions to the burden of paying for health insurance while leaving them to bare alone the cost of non-emergency but expensive medical care–the worst of all worlds.

I really value how you’ve teased out the many disincentives for providing access to care for all (the touted primary purpose of the legislation), particularly a physician’s (understandable) desire to keep quality of care scores up–even at the cost of rejecting patients. Ack.

A couple of ancillary issues:

1. The growing consolidation of health care markets (especially hospitals, insurers, and medical groups. We are seeing a rapidly-growing integrated vertical health industry. What effect will that/has that consolidation have/had on health care access, service, quality, etc? You may want to check this 2013 paper out- http://bit.ly/1bmewbX and this 1/24 article exploring that consolidation as a key driver of health care costs – http://bit.ly/1fnPbxp.

2. As the financial burden of healthcare is a primary reasons Americans file for bankruptcy (and, as you point out, more doctors are going to be leery of providing care to persons not on private insurance), we will likely see an increase in the cost of medical payment credit services, especially for those who can least afford it.

3. The lack of price transparency makes point #2 even more of a problem. It would be one thing if–like a fast-food restaurant–buyers of healthcare could consult the menu and compare prices. That isn’t the case (and I’m not expecting to see that change anytime soon.

4. Finally, Issues of health literacy come in to play and, even though IOM said way back in 2010 that “Individuals with low levels of health literacy are least equipped to benefit from the ACA, with

potentially costly consequences for both those who pay for and deliver their care, as well as for themselves” (http://bit.ly/1eLNwjT), we aren’t seeing the massive education process the IOM called for. I think the true and cost(s) of that lack is going to be quite ugly.

Thanks again.

Angela

Thanks so much for your insightful comments, Angela. It’s distressing to me to see how little progress has been made to make health care in this country more equitable. When I stand back and look at things historically — not just the history of health care but the tradition of blindingly assuming everyone has an equal opportunity — I can see how we got here. But that doesn’t make it any easier to be optimistic about the future.

That Robert Wood Johnson study looks excellent. Thank you for both of those links.

Jan