I’m generally sympathetic to the benefits of alternative therapies. That’s not surprising given I’ve studied, practiced, and taught alternative therapies, in addition to having a PhD in the History of Science and Medicine. There are times, however, when I totally understand why some members of the medical profession are so vehement in their condemnation of alternative “medicine.”

I’m generally sympathetic to the benefits of alternative therapies. That’s not surprising given I’ve studied, practiced, and taught alternative therapies, in addition to having a PhD in the History of Science and Medicine. There are times, however, when I totally understand why some members of the medical profession are so vehement in their condemnation of alternative “medicine.”

Case in point: A recent post on KevinMD, in which Dr. Amy Tuteur writes: “‘Alternative’ health practitioners are nothing more than quacks and charlatans and their ‘remedies’ are nothing more than snake oil. The fact that anyone in this day and age still believes in such crackpot theories is a tribute to the power of ignorance and superstition.”

Such an extreme denunciation throws the baby out with the bathwater. I’m sympathetic to the emotion expressed here, however, because I know that some people with life-threatening diseases use alternative treatments exclusively following their diagnosis. By the time their disease has advanced and they’re willing to use, or in some cases capitulate to, conventional medicine, it’s too late. I have a dear friend who unfortunately did just that and passed away earlier this year.

Examples like this, and there are many, understandably strengthen medical opposition to any and all alternative therapies. But are alternative therapies themselves the problem, or is it a matter of how they’re used and how they’re positioned within the broad therapeutic spectrum?

Aesthetics vs. reason

There’s a problem right at the start with the word “alternative,” especially when it’s taken too literally by those seeking cures or other health benefits.

‘Alternative’ too easily suggests two independent alternatives: one, scientific biomedicine, the other, a variety of “alternative” or “holistic” practices. “Alternative” practices, by definition, aren’t based on rigorous scientific evidence — If they were, they would be part of medicine.

It may seem irrational to choose an alternative approach when health and life clearly depend on what conventional medicine can offer. But that’s not how patients see it. Those who resist and distrust modern medicine can provide abundant reasons for taking an alternative path. Many of the reasons for choosing alternative over medical treatment, however, are based on anecdotal evidence or perhaps on a single scientific study that wasn’t peer reviewed or hasn’t been repeated.

The alternative/biomedicine decision is more often based on aesthetic values than reason. It’s aesthetic in the sense that most clients seeking alternative therapies are looking for something that’s consistent with the values of their life style and world view: “natural,” holistic, non-invasive, respectful of the individual, and conscious of the environment.

Art and science

A mere century ago, medicine wasn’t a science, but an art. It had a great deal in common with traditional therapies – those now considered alternative. In an attempt to separate itself and prove its scientific worthiness, much of the art of medical practice has been abandoned. Yet for all that medicine has “grown up” and taken its place among the sciences, the medical profession itself acknowledges that “the portion of medicine that has been proven effective is still outrageously low — in the range of 20% to 25%.”

Many devotees of alternative practices are aware of the dangers of medicine. The Institute of Medicine released a report in 2000 called “To Err Is Human.” One study included in the report estimates that as many as 98,000 patients die every year from medical errors. Hospitals, in particular, are especially prone to errors.

Alternative therapies offer a healing relationship

Just because some individuals risk their health by choosing alternative treatments doesn’t mean all alternative therapies should be outlawed, as some extremists recommend. The popularity of alternative health care should prompt the medical profession to ask why so many people find it preferable. There are many valid reasons, including a search for a healing relationship that, not so long ago, was the foundation of professional medicine.

Unfortunately, alternative approaches to health are littered with practitioners who intentionally take advantage of the fear that surrounds disease and death. When people are sick, they’re afraid. Fear and anxiety are easily manipulated and amplified. Some alternative practitioners specialize in doing precisely this, usually in order to sell their products and services. They give all alternative therapies a bad name.

In the next post, a prime example of an alternative practitioner who deserves condemnation from conventional medicine.

Related posts:

Why it’s safe to completely ignore Dr. Mercola

The Spleen in Chinese Medicine

The doctor/patient relationship: What have we lost?

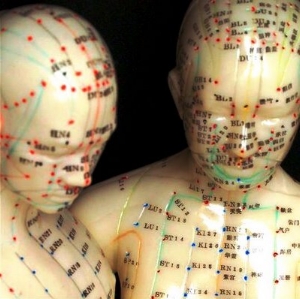

Image source: Urban Acupuncture

Sources:

(Links will open in a separate window or tab.)

Amy Tuteur, MD, The alternative, complementary, and integrative health obsession with toxins, KevinMD, October 8, 2009

Medical Guesswork, Business Week, May 29, 2006

Institute of Medicine, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, 2000

Dear Jan,

nihil novum sub sole…

Take a look at the link I posted.

Ciao, best regards.

Stefano M.

Thank you, Dr. Marcelli, for your comment. Here is the link to your page that describes the correspondence between the circle in the Kidney channel at the inner ankle and the seminal and urinary paths.

I was interested in your comments on how the ancient Chinese discovered the pathways. There are modern teachers who claim they can feel the location of the pathways when they are in deep meditation. So one theory is that the ancient Chinese, who presumably also engaged in deep meditation, were able to visualize the pathways.

I also enjoyed your page on the back-shu points. Since you’re interested in fetal development, you might find this interesting. I was taught that the reason specific back-shu points correspond to the different channels is that they are the locations where the energy of each of these channels first entered the body during fetal development. I was also taught that the Dumai and Renmai correspond to the first cellular division of the fertilized egg.

Other teachers may disagree, but one of the things I so respect about Chinese Medicine is its ability to tolerate divergent interpretations of the body and health. Conflicting theories can be equally effective, in contrast to the extreme reductionism of modern scientific medicine.

I teach acupressure at Kaiser Permanente. We use a tool that allows students to reach points on the back. I always tell students that if they do nothing more than stimulate the back-shu points, they will be benefiting the entire body.

I also enjoyed the photo of the tail on the 8-week old embryo. This has particular significance for me. When I was a child, I overheard the idea that the human fetus passes through the developmental stages of lower animals (gills, tail, yolk sac), the “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” theory of Ernst Haeckel. Since I was at a very impressionable age, it had a big impact on my beliefs about evolution and the teachings of religion. That experience helps me understand why the religious right does not want children to learn about evolution.