In the July issue of Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences:

- A comparison of 19th century public health measures and the contemporary approach to the AIDS pandemic

- The conflict between the medical profession and religion in their attempts to portray habitual drunkenness

- The understanding of dementia paralytica in the Netherlands at a time when psychiatry was attempting to establish itself as a medical profession

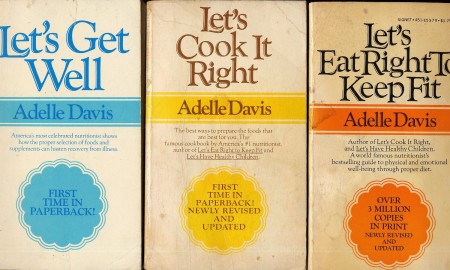

- Adelle Davis’ role in creating the ideology of nutritionism.

There’s also a commentary on the Adelle Davis article, an ‘In Memoriam’ for Sherwin B. Nuland, and reviews of ten books (of which I’ve featured here only two).

Thanks to h-madness (a great blog) for bringing my attention to this new issue. Somatosphere (a most excellent blog — highly recommended) often covers this journal, but I haven’t yet seen the July issue there, so I’ll go ahead and post these abstracts. Note that all articles (other than their abstracts/extracts) are behind a paywall. (emphasis added in what follows)

Articles

The AIDS Pandemic in Historic Perspective

Powel Kazanjian

Potent antiretroviral drugs (ART) have changed the nature of AIDS, a once deadly disease, into a manageable illness and offer the promise of reducing the spread of HIV. But the pandemic continues to expand and cause significant morbidity and devastation to families and nations as ART cannot be distributed worldwide to all who need the drugs to treat their infections, prevent HIV transmission, or serve as prophylaxis. Furthermore, conventional behavioral prevention efforts based on theories that individuals can be taught to modify risky behaviors if they have the knowledge to do so have been ineffective. Noting behavioral strategies targeting individuals fail to address broader social and political structures that create environments vulnerable to HIV spread, social scientists and public health officials insist that HIV policies must be comprehensive and also target a variety of structures at the population and environmental level. Nineteenth-century public health programs that targeted environmental susceptibility are the historical analogues to today’s comprehensive biomedical and structural strategies to handle AIDS. Current AIDS policies underscore that those fighting HIV using scientific advances in virology and molecular biology cannot isolate HIV from its broader environment and social context any more than their nineteenth-century predecessors who were driven by the filth theory of disease.

“An Army of Reformed Drunkards and Clergymen”: The Medicalization of Habitual Drunkenness, 1857–1910

Katherine A. Chavigny

Historians have recognized that men with drinking problems were not simply the passive subjects of medical reform and urban social control in Gilded Age and Progressive Era America but also actively shaped the partial medicalization of habitual drunkenness. The role played by evangelical religion in constituting their agency and in the historical process of medicalization has not been adequately explored, however. A post-Civil War evangelical reform culture supported institutions that treated inebriates along voluntary, religious lines and lionized former drunkards who publicly promoted a spiritual cure for habitual drunkenness. This article documents the historical development and characteristic practices of this reform culture, the voluntarist treatment institutions associated with it, and the hostile reaction that developed among medical reformers who sought to treat intemperance as a disease called inebriety. Those physicians’ attempts to promote therapeutic coercion for inebriates as medical orthodoxy and to deprive voluntarist institutions of public recognition failed, as did their efforts to characterize reformed drunkards who endorsed voluntary cures as suffering from delusions arising from their disease. Instead, evangelical traditions continued to empower reformed drunkards to publicize their own views on their malady which laid the groundwork for continued public interest in alcoholics’ personal narratives in the twentieth century. Meanwhile, institutions that accommodated inebriates’ voluntarist preferences proliferated after 1890, marginalizing the medical inebriety movement and its coercive therapeutics.

Jessica Slijkhuis and Harry Oosterhuis

This article explores the approach of dementia paralytica by psychiatrists in the Netherlands between 1870 and 1920 against the background of international developments. The psychiatric interpretation of this mental and neurological disorder varied depending on the institutional and social context in which it was examined, treated, and discussed by physicians. Psychiatric diagnoses and understandings of this disease had in part a social–cultural basis and can be best explained against the backdrop of the establishment of psychiatry as a medical specialty and the specific efforts of Dutch psychiatrists to expand their professional domain. After addressing dementia paralytica as a disease and why it drew so much attention in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, this essay discusses how psychiatrists understood dementia paralytica in asylum practice in terms of diagnosis, care, and treatment. Next we consider their pathological–anatomical study of the physical causes of the disease and the public debate on its prevalence and causes.

Catherine Carstairs

America’s most widely read nutritionist of the postwar decades, Adelle Davis, helped to shape Americans’ eating habits, their child-feeding practices, their views about the quality of their food supply, and their beliefs about the impact of nutrition on their emotional and physical health. This paper closely examines Davis’s writings and argues that even though she is often associated with countercultural food reformers like Alice Waters and Frances Moore Lappé, she had as much in common with the writings of interwar nutritionists and home economists. While she was alarmed about the impact of pesticides and food additives on the quality of the food supply, and concerned about the declining fertility of American soil, she commanded American women to feed their families better and promised that improved nutrition would produce stronger, healthier, more beautiful children who would ensure America’s future strength. She believed that nearly every health problem could be solved through nutrition, and urged her readers to manage their diets carefully and to take extensive supplementation to ensure optimum health. As such, she played an important role in creating the ideology of “nutritionism” – the idea that food should be valued more for its constituent parts than for its pleasures or cultural significance.

Commentary

Susan C. Lawrence

Since the time of Hippocrates, if not before, authors preoccupied with restoring, maintaining, and enhancing health have advised their readers on when, how, and what to eat. Constant themes have included avoiding excesses of wine, rich meats, and unripe fruit while integrating diet with the practice of other habits—sleep, work, exercise, sex—that deplete or augment the body’s humors/vital powers/energy/immune system. Late-nineteenth and twentieth century scientists hardly discovered the intricate connections between food, health, and illness, but they certainly reshaped them in their laboratories. Early to mid-twentieth century popularizers and manufacturers helped to spread nutritionists’ discoveries and speculations, particularly about vitamins, as we know from Rima Apple’s book, Vitamania (Rutgers, 1996). At the same time, American reformers raised serious concerns about food, with notable worries about malnutrition in children, food safety, and industrial-scale food processing—uneasiness that only intensified after World War II (WWII). The result is our own age of food anxiety: is this bite a “bad” choice or …

Book Reviews

Lotions, Potions, Pills, and Magic: Health Care in Early America by Elaine G. Breslaw

Reviewed by Melissa Grafe

Many histories chronicle American medicine’s transformation from its chaotic and disorganized beginnings into “scientific medicine” in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. By synthesizing secondary sources in a tightly packed two hundred pages, Elaine Breslaw resists retelling this triumphalist narrative and instead focuses much needed attention on medicine and health in America before the Civil War.

Breslaw’s narrative is not a cheery one. While she examines the many sides of the “American experience” of healthcare and medicine, it is the role of the doctor that drives the story. Breslaw condemns the medical profession in her synthesis, attributing the decline of healthcare in the nineteenth century to the practices of orthodox medicine. She argues that “the medical profession in America failed to improve health and often became a stumbling block to advances in medicine” (4). Breslaw’s argument depends upon and expands Ronald Numbers’s essay, “The Fall and Rise of the American Medical Profession” (1985), focusing specifically on the “fall” and the reasons American medicine declined in status in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Breslaw ranges over a wide variety of topics in ten chapters. The first two …

Reviewed by John P. Swann

Dominique Tobbell’s contribution to the expanding corpus of drug studies, Pills, Power, and Policy, is a thoughtful, well researched, and refreshingly well-written study of how a variety of interests shaped drug regulation during the crucial period from the 1950s through the 1970s. Relying on an array of primary source material, trade literature, massive Congressional hearings, and most of the relevant secondary sources, the author carefully crafts the story of how the pharmaceutical industry cultivated scientific and professional alliances that it later used to resist and modify efforts by Congress, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and therapeutic reformers to impose stricter controls on drugs. This book is a model of how to capture the intricacies and broad impact of those who have tried to influence policy from outside the government.

Tobbell begins by focusing on Merck and Company as a case study of how the pharmaceutical industry developed knowledge networks with the academic research community. Merck was one of the most well-regarded, research pharmaceutical firms since the 1930s, supporting and collaborating with outside researchers, sponsoring postdoctoral fellowships, and offering a working environment for its own scientists that …

Also reviewed:

Picturing the Book of Nature: Image, Text, and Argument in Sixteenth-Century Botany and Anatomy by Sachiko Kusukawa

Fevered Measures: Public Health and Race at the Texas–Mexico Border, 1848–1942 by John McKiernan-González

Deluxe Jim Crow: Civil Rights and American Health Policy, 1935–1954 by Karen Kruse Thomas

Exclusions: Practicing Prejudice in French Law and Medicine, 1920–1945 by Julie Fette

American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic by Nancy K. Bristow

The Morning After: A History of Emergency Contraception in the United States by Heather Munro Prescott

Saving Babies?: The Consequences of Newborn Genetic Screening by Stefan Timmermans and Mara Buchbinder

The Genealogical Science: The Search for Jewish Origins and the Politics of Epistemology by Nadia Abu El-Haj

Related posts:

The tyranny of health then and now

When healthy eating becomes unhealthy

What we used to eat

What’s wrong with our food?

Are the most heavily marketed drugs the least beneficial?

Medicalization then and now

Image source: Bubbe Wisdom

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.