Continued from the previous post, where I noted that the Lalonde report — despite its good intentions — was followed by an emphasis on healthy lifestyles and personal responsibility for health, as well as increased health care costs.

Continued from the previous post, where I noted that the Lalonde report — despite its good intentions — was followed by an emphasis on healthy lifestyles and personal responsibility for health, as well as increased health care costs.

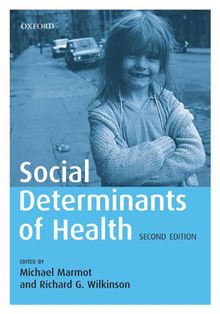

Personal responsibility and social class

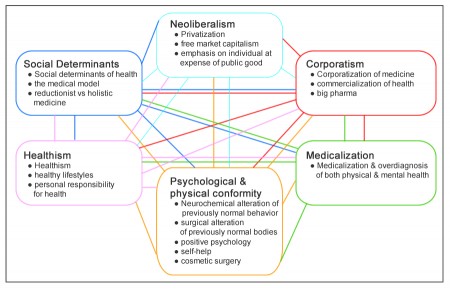

In Why Are Some People Healthy and Others Not?, Marmor et al, writing in 1994, were disappointed that the Lalonde report had not effectively prompted governments to address the underlying causes of health and disease. One reason for this, they believed, was that health policy reflects public opinion. If the public holds traditional views on what makes us sick (pathogens), what prevents disease (medical care), and what we can do to be healthy (take personal responsibility), new policies that include social determinants are unlikely. Those who are on the forefront of professional, scientific opinion may very well understand the importance of social determinants, but public opinion changes slowly. Without an education program, such as the relatively successful anti-smoking campaign, the public is unlikely to endorse change.

This is certainly true, although I believe there’s also something more fundamental at work here, namely, how a society accounts for the different life outcomes of its citizens. In Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life, Annette Lareau describes the assumptions people make when they hold others personally responsible for their life circumstances. Read more