Here’s an idea I found interesting. The author, Bruno Latour, calls it a “plausible fiction.” (emphasis added)

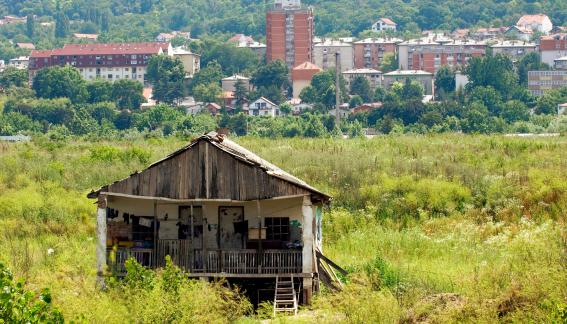

The enlightened elites—they do exist—realized, after the 1990s, that the dangers summed up in the word “climate” were increasing. Until then, human relationships with the earth had been quite stable. It was possible to grab a piece of land, secure property rights over it, work it, use it, and abuse it. The land itself kept more or less quiet.

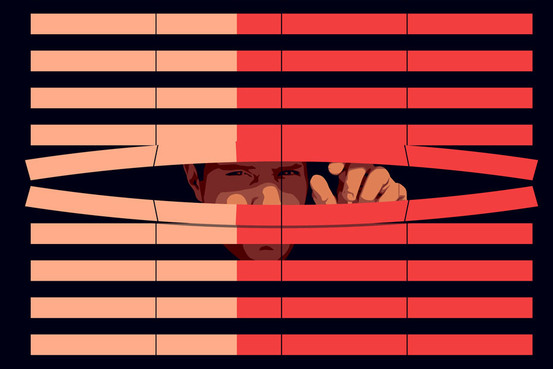

The enlightened elites soon started to pile up evidence suggesting that this state of affairs wasn’t going to last. But even once elites understood that the warning was accurate, they did not deduce from this undeniable truth that they would have to pay dearly.

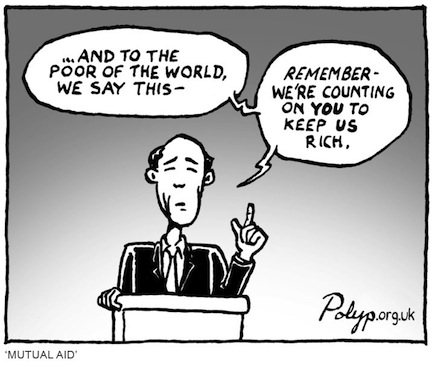

Instead they drew two conclusions, both of which have now led to the election of a lord of misrule to the White House: Yes, this catastrophe needs to be paid for at a high price, but it’s the others who will pay, not us; we will continue to deny this undeniable truth.

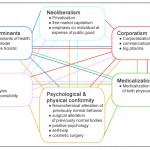

If this plausible fiction is correct, it enables us to grasp the “deregulation” and the “dismantling of the welfare state” of the 1980s, the “climate change denial” of the 2000s, and, above all, the dizzying increase in inequality over the past forty years. All these things are part of the same phenomenon: the elites were so thoroughly enlightened that they realized there would be no future for the world and that they needed to get rid of all the burdens of solidarity as fast as possible (hence, deregulation); to construct a kind of golden fortress for the tiny percent of people who would manage to get on in life (leading us to soaring inequality); and, to hide the crass selfishness of this flight from the common world, to completely deny the existence of the threat (i.e., deny climate change). Without this plausible fiction, we can’t explain the inequality, the skepticism about climate change, or the raging deregulation.