I recently read and very much enjoyed Pascal Bruckner’s newly translated book, Perpetual Euphoria: On the Duty to Be Happy

I recently read and very much enjoyed Pascal Bruckner’s newly translated book, Perpetual Euphoria: On the Duty to Be Happy (originally published in 2000). Here’s a passage from the chapter “The Fat, Prosperous Elevation of the Average, the Mediocre.” (emphasis added in the following quotations)

[W]hat a contradiction to see in civil unions or in gay marriage with adopted children the forerunners of the disintegration of the family! It is exactly the reverse: it is the familial order that is triumphing over all of us, no matter what group or belief we subscribe to, and it is hard to see any argument, anthropological or other, that we could make against it.

Good point. Lost on conservatives, unfortunately. The new normal in family formation is resisted by those who cling to traditional values, while the traditional value of family prevails.

The paragraph continues with a discussion of conformity and anticonformity, and includes the following footnote:

According to Lucien Sfez, in 1995, 45 percent of literature majors at Stanford said they were gay, a figure that has little to do with reality. The author sees three reasons for this phenomenon: it is cool to say you’re gay and not to have the brutal image of the heterosexual; gays being a minority are protected by labor unions; and finally, gays cannot be accused of sexual harassment. La Santé parfait, p. 65.

The first reason makes sense, the second is irrelevant today, and the third certainly isn’t true in the US.

The footnote appears in connection with a critique of identity politics. “People state their identities only to make others yield, and display them noisily, perhaps out of fear that without them they would not exist.” Later on, however, in a chapter on suffering, Bruckner does not fault those who go public with an identity that features an incurable disease or disability.

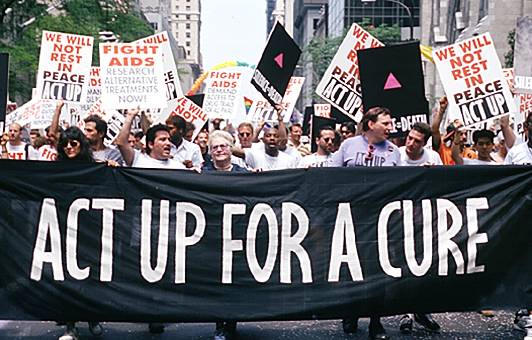

The impact of AIDS activism on attitudes towards illness

Our relationship to both health and illness changed profoundly in the late 20th century. Bruckner describes the role of AIDS activism in this transition.

Something tiny but decisive may have changed in our relationship to illness. We fear it and avoid it as much as ever, but we are no longer willing to be dispossessed of it by an outside authority, whether medical or other; henceforth we demand to be associated as much as possible in the process of caring for ourselves. … AIDS not only revived the old association between sex and death …. It brought into confrontation two universes that no longer had anything to do with each other, youth and the tomb, at the end of a century that had promised us all that we would live, if not forever, at least to the age to 120. … [G]enerations of viruses were waiting in the shadows to kill us. … [I]t put an end to the myth of medical omnipotence and restored a terrible meaning to the word “incurable.” …

AIDS acquired a special status, half-political, half-medical. … It is perhaps thanks to AIDS … that patients have become legal and social actors (and no longer simply passive objects in the hands of physicians).

The age of paternalism in the doctor-patient relationship is a thing of the past in the US. In other countries that change is just now happening. For example, this comment from a doctor in Singapore: “The paternalism that largely characterises Asian healthcare today is increasingly unwelcome by patients who want and expect their doctors to be advisors and advocates rather than decision-makers on their behalf.”

What used to be “bad” is now seen as prejudice

AIDS reformulated what it means to be a “victim” of disease or disability, and this new meaning was contagious.

… people who refuse to allow themselves to be reduced to victimhood and who aspire, even in their weakened physical condition, to regain their freedom and responsibility. Rejecting the victimization that argues that a handicap requires special exemptions, they bring their sickness into the public sphere in order to be recognized and to return to normal life: for example, the young French woman aviator who was confined to a wheelchair after an accident and who created a movement to gain acceptance for handicapped pilots. By deciding that a certain abuse is no longer tolerable, and by translating their revolt into legal and political terms, these people modify the norm and shift the threshold of intolerance for everyone.

[B]ecause of the demands made on it by hemophiliacs, cancer patients, AIDS patients, and people with disabilities, a whole society is trying to come to terms with a new problem and to take control over its calamities through a dual effort of pragmatism and sheer determination. … What used to a matter of bad luck is now conceived in terms of prejudices, that is, a “modifiable inevitability” (Ernst Cassirer). … [T]he seriously ill, the traumatized, and accident victims, strong in their common weaknesses, manifest their freedom with regard to what had previously put them in the category of subcitizens, those receiving assistance. They are fighting against the segregation that made them lepers, bearers of bad news. They are fighting to remain members of the human community.

In the Internet age, remaining a member of the human community includes blogging for the duration of a terminal illness. See Blogging Til I Die: A cultural revolution? from Pallimed and Blogger announces own death after battle with cancer from CNN.

Related posts:

Pascal Bruckner on doctors and patients

The duty to be happy

The unavoidable and burdensome responsibility to be happy

Resources:

Image: History of AIDS Activism

Pascal Bruckner, Perpetual Euphoria: On the Duty to Be Happy

Lucien Sfez, La sante parfaite: Critique d’une nouvelle utopie

Blogging Til I Die: A cultural revolution?, Pallimed, April 27, 2010

Katie Silver, Blogger announces own death after battle with cancer. CNN, May 8, 2011

Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.