The New York Times has a five part series on anosognosia, a word of Greek origin where “nosos” means disease and “gnosis” means knowledge (plus the initial “a” for not). Patients with this medical condition don’t know they have a disease and appear unaware of their symptoms, which can be as dramatic as paralysis or blindness to half their visual field.

The New York Times has a five part series on anosognosia, a word of Greek origin where “nosos” means disease and “gnosis” means knowledge (plus the initial “a” for not). Patients with this medical condition don’t know they have a disease and appear unaware of their symptoms, which can be as dramatic as paralysis or blindness to half their visual field.

Reflecting on the condition, the author, Errol Morris, raises a number of interesting questions, such as: Do patients really have no knowledge of their condition? Are incompetent people unable to know they’re incompetent?

He also points out the distinction between the things we know we don’t know (what the weather will be 100 years from now) and the things we’re so unaware of we don’t even know we don’t know them (unnameable by definition). He cites the now-famous words of Donald Rumsfeld: “There are things we know we know about terrorism. There are things we know we don’t know. And there are things that are unknown unknowns. We don’t know that we don’t know.”

Everyday anxiety alludes to the suspicion that meaning and value are arbitrary

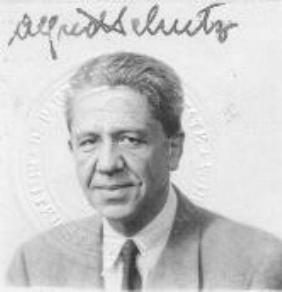

The concept of negative knowledge – what we know we don’t know and what we don’t know we don’t know — was discussed by Alfred Schutz in his The Phenomenology of the Social World (1932). Thirty years ago, after reading Schutz, I wrote about negative knowledge as it relates to anxiety.

Taken one by one, we can always find an explanation for our ignorance once we become aware of it. What we don’t admit is that we’re not dealing with special cases. What we consider a technical inadequacy (I just haven’t learned that yet, I can’t know the future before it arrives) is in fact a characteristic of all knowledge. All “definitive” solutions are subject to change. Whatever we know today borders on how we will know it differently in the future. This is well known to anyone who studies the history of science.

In practice there’s no reason to suspect that any particular piece of information is inadequate before it is revealed to be otherwise. But in theory there’s no reason to exclude anything from suspicion. It is characteristic of all interpretations, meanings, and values that they are never the last word. They are all potentially obsolete. Reality is not just occasionally precarious – it has no permanent foundations whatsoever. It is the nature of knowledge to be fragmentary and partial. This is the first and final, the ultimate source of anxiety.

The fringe of negative knowledge that surrounds what we know blends into the region of the fundamentally opaque and unknowable, what is beyond our ability to grasp. Every relative insufficiency of knowledge refers to the more basic inadequacy of a humanly created world. Negative knowledge imperceptibly shades into the inexpressible limits of knowledge. Everyday anxiety is the first drop of what could turn into a flood of realization that would drain the reservoir of meaning – the recognition that all meaning and value is arbitrary.

In radicalizing the problems of psychology we reach the philosophical dimension

Ignorance – lack of knowledge – is a subject worthy of investigation in itself. Here’s a portion of the product description for a book of essays, Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance, edited by Robert Proctor and Londa Schiebinger:

Agnotology—the study of ignorance—provides a new theoretical perspective to broaden traditional questions about “how we know” to ask: Why don’t we know what we don’t know? … [I]gnorance is often more than just an absence of knowledge; it can also be the outcome of cultural and political struggles. Ignorance has a history and a political geography, but there are also things people don’t want you to know (“Doubt is our product” is the tobacco industry slogan). … The goal of this volume is to better understand how and why various forms of knowing do not come to be, or have disappeared, or have become invisible.

In addition to the political, cultural, and economic influences on ignorance, there is the ignorance alluded to by psychological considerations: the inability to explain anosognosia, the experience of existential anxiety. The New York Times series on anosognosia would have appealed to Schutz, as well as to his friend and colleague, Aron Gurwitsch. As Gurwitsch once wrote: “By a sufficient radicalization of the problems of psychology we reach the philosophical dimension.”

Related posts:

Paging Dr. Frankenstein

The last well person

“I” Is for Innocent: Health obsession in fiction

Should the medical establishment regulate psychotherapy?

My personal odyssey through the health culture

Resources:

Photo source: Center for Advanced Research in Phenomenology

Errol Morris, The Anosognosic’s Dilemma: Something’s Wrong but You’ll Never Know What It Is (Part 1), The New York Times, June 20, 2010

Alfred Schutz, Phenomeology of the Social World

Robert Proctor and Londa Schiebinger (eds), Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance

Alfred Schutz (edited by Richard Grathoff), Philosophers in Exile: The Correspondence of Alfred Schutz and Aron Gurwitsch, 1939-1959

Aron Gurwitsch, Studies in Phenomenology and Psychology

Jan Henderson, ”Don’t Worry”: Understanding Anxiety

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.