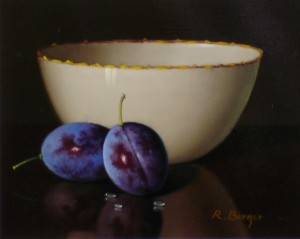

I have eaten

I have eaten

the plums

that were in

the icebox

and which

you were probably

saving

for breakfast

Forgive me

they were delicious

so sweet

and so cold

— William Carlos Williams

William Carlos Williams is part of an honorable tradition in the history of medicine — the physician/poet. He followed the example set by previous physician/poets, such as John Keats, Friedrich Schiller, and Oliver Wendell Holmes (of “Chambered Nautilus” fame). Physicians have also been writers, painters, musicians, philosophers, and – since the 19th century – photographers.

Yet in 1980 the historian G.S. Rousseau expressed concern that modern physicians no longer embodied the humanist tradition of their predecessors. Now that medicine had overwhelmingly become a science and not an art, he claimed, the interests and accomplishments of physicians had narrowed. (emphasis added)

In our century nothing has influenced the physician’s profile more profoundly than the loss of his or her identity as the last of the humanists. Until recently, physicians in Western European countries received broad, liberal educations, read languages and literature, studied the arts, were good musicians and amateur painters; by virtue of their financial privilege and class prominence they interacted with statesmen and high-ranking professionals, and continued in these activities through their careers. It was not uncommon, for Victorian and Edwardian doctors, for example, to write prolifically throughout their careers: medical memoirs and auto-biographies, biographies of other doctors, social analyses of their own times, imaginative literature of all types.

In twentieth-century America, the pattern has changed; only the most imaginative physicians can hope for this artistic lifestyle as a consequence of the economic constraints and housekeeping demands placed upon the doctor …. [T]he diminution of ‘humanist’ content in the training of physicians has lent an impression – perhaps falsely so but nevertheless pervasively – that medics are technicians, anything but humanists. As a by-product, it has nurtured a myth (already old by the eighteenth-century Enlightenment) that medicine is predominantly a science rather than an art. Both notions require adjustment if physicians hope to return to their earlier enriched, and probably healthier, role.

Rousseau’s comment on constraints (for “housekeeping demands” substitute “dealing with insurance”) is even more true today, especially for primary care physicians. A liberal education that values the humanist tradition is also in danger. See, for example, Martha Nussbaum’s Not For Profit, where she writes that contemporary education favors profitable, market-driven, career-oriented skills and devalues imagination, creativity, and critical thinking – qualities essential to the art and science of medicine.

But Rousseau’s assessment that physicians lack artistic interests is simply not true. Physicians continue to be prolific in their contributions to the ‘humanist’ tradition, most visibly as writers.

A plethora of physician/writers

We may no longer have physician/poets who will be as well known to posterity as William Carlos Williams, but physician/writers are not only widely read. They are influential. During the debate over health care reform, President Obama distributed Atul Gawande’s New Yorker article on McAllen, Texas as required reading for his staff. For Gawande’s work on surgical safety checklists, described in his book The Checklist Manifesto, The Lancet nominated him to the class of doctors who have saved the most lives.

Physicians write not only nonfiction, but literature. This past year I’ve read Frank Huyler’s novels, Right of Thirst and The Laws of Invisible Things

, as well as his collection of sensitive essays, The Blood of Strangers: Stories from Emergency Medicine

.

I read Abraham Verghese’s novel, Cutting for Stone. Verghese, whose Amazon biography says he “sees patients, teaches students and writes,” published numerous public commentaries during the health care debate.

Alexander McCall Smith is not a physician per se, but, as a professor of medical law and an expert on bioethics, he falls within the family of medicine. He’s widely known for his The No.1 Ladies’ Detective Agency series and has recorded an amusing lecture called Confessions of a Serial Novelist

. I counted 62 books on his Wikipedia page, including his academics texts and children’s books.

The topic “Physician writer” has its own entry on Wikipedia, with over 130 authors listed for the 20th century (A. J. Cronin, Walker Percy, Lewis Thomas, Michael Crichton, Robin Cook, Oliver Sacks, Sherwin Nuland, Danielle Ofri, Samuel Shem (The House of God)). The prolific Jerome Groopman isn’t even listed. Nor are many of my personal favorites: Sandeep Jauhar (Intern: A Doctor’s Initiation

), David Watts (The Orange Wire Problem

), Lisa Sanders (Every Patient Tells a Story

), H. Gilbert Welch (Should I Be Tested for Cancer?

), and Robert Martensen (A Life Worth Living

).

What’s different in the 21st century?

And then there’s blogging. A list of the top 50 blogs by physicians divides websites into The Human Side (Musings of a Dinosaur), Specialties (Bioethics Discussion Blog), American Issues (KevinMD), and Other Countries (Bad Medicine). Another top-50 list includes the health care industry, nurses, psychiatry, radiology, and alternative medicine. And look at the amount of writing on George Lundberg’s creation, Medscape.

Physician/writers are not only almost too numerous to count, but there’s ample evidence of their broad humanist interests. Each issue of JAMA includes both a poem and an essay by a physician (occasionally by a patient), plus a discussion of the art work on the cover. The New England Journal of Medicine publishes photos by physicians who have visited distant lands or observed exotic wildlife. Yale Medical School publishes the online Journal for Humanities in Medicine. Pallimed — a blog on palliative care medicine — has a separate blog for Arts & Humanities. Pulse is an online journal of “personal accounts of illness and healing fostering the humanistic practice of medicine.” And Danielle Ofri writes on how she uses poetry to good effect during hospital rounds.

For physicians who are also visual artists there’s the American Physicians Art Association, established to “encourage and assist the establishment of local, regional physician art organizations and exhibits.”

For physician/musicians there are orchestras staffed solely by the medical profession. The Doctors Orchestral Society of New York, for example, and the Albert Einstein Symphony Orchestra, also in New York. The Philadelphia Doctors Chamber Orchestra, Boston’s Longwood Symphony Orchestra, and the Los Angeles Doctors Symphony Orchestra. Nearly every major US city has an orchestra staffed by the medical profession. The same is true for countries around the world: Orquestra “Ars Medica” in Barcelona, Physicians Chamber Orchestra of Taiwan, Orchestra Medicus Japan. There’s a long list at OrchestraDocs.

Plus, one does not have to be an artist oneself to be a physician/connoisseur of the arts. A fictional example is the neurosurgeon in Ian McEwan’s novel Saturday, who works his way through literature recommended by his daughter, the poet, and attends rehearsals of his son, the musician.

The Internet

Was there really a dearth of humanist physicians as recently as 1980? In retrospect it appears Rousseau was overly pessimistic. Physicians now readily share their thoughts and find fellow artists on the Internet. In turn, the artistic endeavors of physicians can be discovered and widely appreciated by an ever expanding audience. There seems little reason to fear that today’s physicians are mere technicians, lacking in imagination and creativity and with little interest in the arts and humanities. Physicians today are as active in the arts as they ever were, though I do wonder — like Rousseau — how those who continue to practice their profession manage to find the time.

Encore: Physician Friedrich Schiller’s Ode to Joy

The words for Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy,” from his Symphony No. 9, were written by physician/poet Friedrich Schiller. The first video is a moving performance conducted by Leonard Bernstein. The second is a much shorter (and quite amusing) version by the Muppets.

Related posts:

The physician as poet

The physician as reader of poetry

We’re all on Prozac now

Ich Habe Genug on Thanksgiving

My limbs are made glorious

Resources:

Image: Original Paintings

G.S. Rousseau, Literature and medicine: towards a simultaneity of theory and practice, Literature and Medicine, 1980 (5) pp. 152-181, as quoted in Michael Neve, Medicine and Literature, Companion Encyclopedia of the History of Medicine, edited by W.F. Bynum and Roy Porter, p. 1521.

Abigail Zuger, M.D., Doctors Who Wield the Pen to Heal the Profession, The New York Times, May 15, 2007

Abigail Zuger, When a Doctor Is More, and Less, Than a Healer, The New York Times, August 24, 2009

Stephen J. Dubner, When Doctors Write, The New York Times, March 28, 2007

Stephen J. Dubner, When Doctors Write, Part II, The New York Times, May 21, 2007

Howard Markel, MD, A Book Doctors Can’t Close, The New York Times, August 17, 2009

Danielle Ofri, Poetry that your patient can appreciate, KevinMD

Medicine: Doctors of Verse, Time, January 15, 1945

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.