If statistical analysis shows conclusively that morbidity and mortality are directly related to income, what should a (presumably) enlightened government do with this information? One approach, consistently popular throughout history, is to blame the victims.

If statistical analysis shows conclusively that morbidity and mortality are directly related to income, what should a (presumably) enlightened government do with this information? One approach, consistently popular throughout history, is to blame the victims.

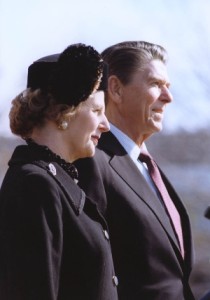

In the Reagan/Thatcher years we saw an enthusiastic promotion of taking personal responsibility for one’s health. Personal responsibility follows naturally from a neoliberal agenda: Deregulation, privatization, a free market economy. Neoliberalism champions the autonomous individual, whose responsible or irresponsible behavior relieves the state of any responsibility.

This theme is vigorously echoed today by Sarah Palin. You can even buy her “personal responsibility” bumper stickers, mugs, and t-shirts to promote the cause.

Personal responsibility is the conservative answer to public ownership of the structural inequities in society. As a political position, it has deep roots. Just as health inequalities are timeless, so is resistance to improving the health and welfare of the poor.

Prejudice and politics

Opposition to health reform that would be of benefit to the poor takes two forms. One is the psychological/philosophical attitude that claims the poor have only themselves to blame for their situation in life and that they are unworthy of assistance.

The second form is the political position that justifies this attitude. The claim is that any coordinated action on the part of government would interfere with the autonomy of states, cities, and individuals. Individuals, cities, states, and whole nations should be able to take personal responsibility for their actions. Those who do not are undeserving of sympathy.

These two forms of opposition are closely intertwined. Here are some examples from the nineteenth century – before the age of political correctness – when politicians and editorialists did not hesitate to display their attitude towards the poor.

Cholera is the best of all sanitary reformers

The first British Public Health Act of 1848 established a central public-health authority that aimed to improve sanitation. (For a description of sanitary conditions in 19th century Britain, see my last post.) Any town with a death rate above 23 per 1000 was required to have such things as drinkable water and sewage removal.

There was considerable opposition to this. One newspaper wrote: “We prefer to take our chance with cholera and the rest rather than be bullied into health.”

Dorothy Porter writes about the pushback:

Opposition … came … from outraged defenders of local government autonomy and those who opposed ‘despotic interference’ in the lives of individuals and the free relations of the economic market. The Tory [conservative] press raged against ‘paternalistic’ government. The Herald believed that ‘A little dirt and freedom may after all be more desirable than no dirt at all and slavery,’ and the Standard suggested that the country had ‘heard enough of the effect of centralization in the New Poor Law.’ Local ratepayers resented being dictated to by a ‘clean party.’

The same newspaper that argued for taking its chances with cholera was not afraid to state its attitude towards the poor quite bluntly: “Cholera is the best of all sanitary reformers.”

The poor — a “race apart” — are uncivilized

Here’s an example of the political case for personal responsibility from early 19th century France:

The French philosopher and politician Constantine Volney (1757-1820) argued that it was the responsibility of all citizens to maintain their health for the benefit of the state. France, he argued, was a collective whole made up of political and economic units – the individual French citizens. Therefore, it was the duty of citizens, regardless of economic status, to be restrained in their consumption of pleasures, to control their display of passions, and to maintain high standards of cleanliness.

Another example from 19th century France that blames the poor for their own condition:

Louis Villermé (1782-1863), the French physician who discovered the relation between income and death rates in early 19th century Paris, believed that the poor were a “race apart.” This, he asserted, accounted for their increased rate of death and disease.

When confronted with the argument that the industrialization of civilization was producing the conditions that created poverty, Villermé and his associates answered simply that the problem was not civilization. The problem was that the poor were uncivilized.

The cause of poverty was the poor themselves. They needed a program of moral regeneration — religious indoctrination to improve their behavior. Through Christian example and education, the poor could be reformed into civilized citizens, leading respectable lives. Through religious education, the poor would cultivate social and hygienic habits worthy of civilization’s moral standards.

Feeding stray animals: Condescension thrives in 2010

William Farr (1807-1883), a British epidemiologist, opposed financial assistance to the poor because it would be spent “indiscriminately upon the idle, reckless, vicious as well as the good but unfortunate.”

For comparison, here’s a statement from Andre Bauer, the Lieutenant Governor of South Carolina, made in January 2010. He makes an analogy between government assistance and feeding stray animals.

My grandmother was not a highly-educated woman, but she told me as a small child to quit feeding stray animals. You know why? Because they breed. You’re facilitating the problem. If you give an animal or a person ample food supply, they will reproduce, especially ones that don’t think too much further than that, and so what you gotta do is you gotta curtail that type of behavior. They don’t know any better.

In defense of his statement, Bauer later remarked: “There’s a big difference between being truly needy and truly lazy.” Compare that to William Farr: Spending “indiscriminately upon the idle, reckless, vicious as well as the good but unfortunate.”

Morally we appear to have made zero progress in 200 years. We should be outraged and ashamed.

Related posts:

Health inequities: An inhumane history

Health care inequality: The US vs. Europe

Health inequities, politics, and the public option

A reason for health care reform

Sources:

Bauer: Welfare Like ‘Feeding Strays;’ NAACP Reacts, WYFF.com, January 27, 2010

Dorothy Porter, Public Health, in W.F. Bynum and Roy Porter, Companion Encyclopedia of the History of Medicine, Vol. 2, p 1231-1261.

Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.